Six Lessons Learned from Teaching English

Dear Abby,

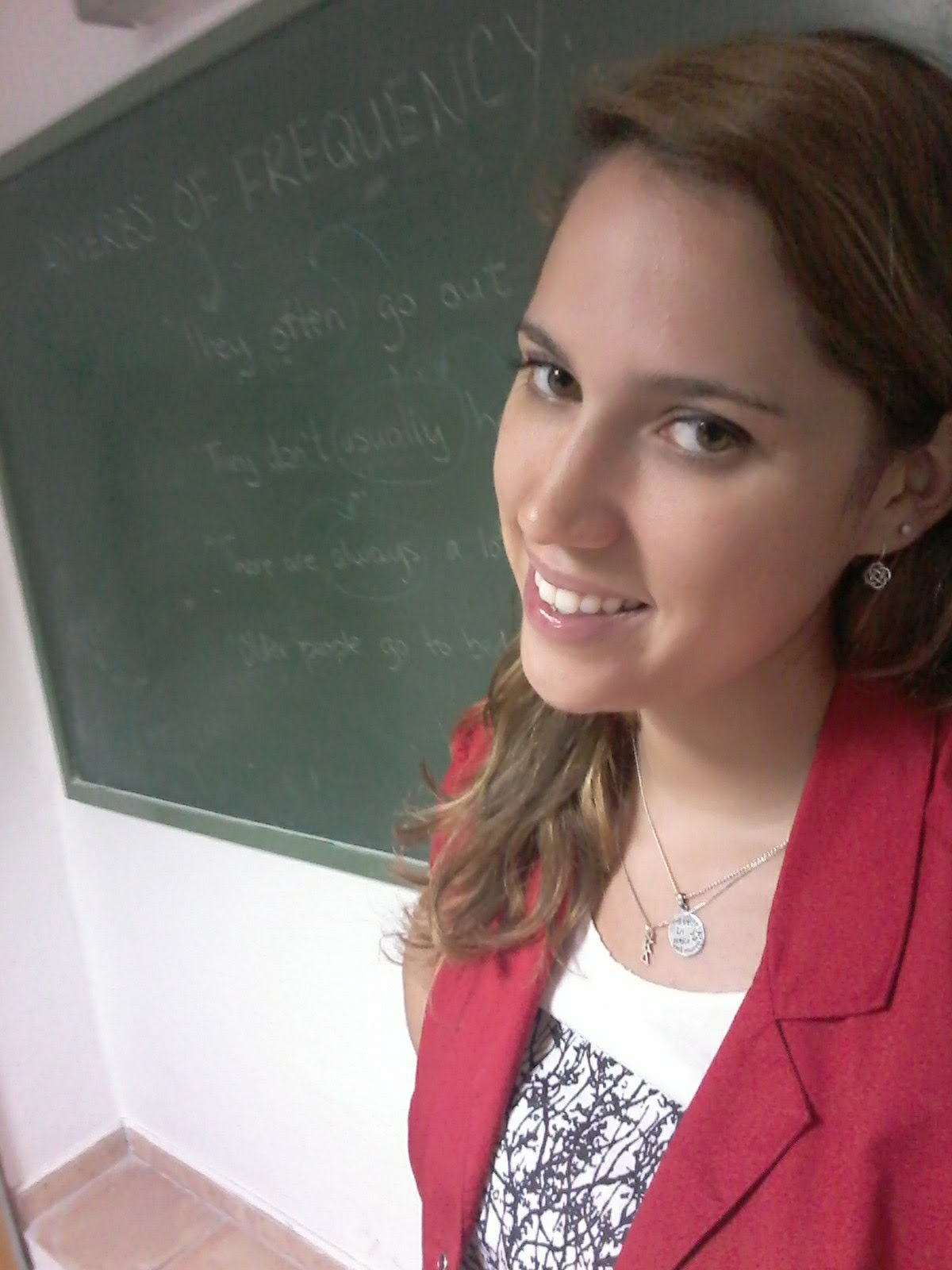

As I got to talk about on the recent episode of The Wanderlusters Mind podcast, teaching English really has opened my mind to new perspectives, life lessons, and my personal application of my own language. It’s somewhat of a cliche to say the best way to learn is to teach, but it has truly been the reality I’ve experienced throughout the last five years of teaching! Preparing for my interview, I got thinking about a lot of lessons learned so far on my journey and I wanted to share some more with you today.

1.) Just because English is your first language doesn’t make you a good teacher:

1.) Just because English is your first language doesn’t make you a good teacher:

Living in Spain, I’ve experienced firsthand how much Spaniards (and most everyone I’ve met who’s learning English) prioritize the fact that their tutor is a native speaker over everything else. While this is greatly to my advantage, I have felt disheartened for my non-native friends who I know would make great teachers.

At times, it’s even embarrassing how easy it is for me to find work in a country whose economy and job market isn’t the strongest simply because I’m a native English speaker. Thus, I’ve changed my attitude about teaching English a lot since I first began. During my first year as an auxiliar and even my first year as the main teacher for small classes I didn’t realize how little I knew about the tricky stuff. Zero vs. first vs. second vs. third conditional? Phrasal verbs? We simply didn’t learn this stuff as native speakers, but students expected me to be able to explain it. Now that I’ve invested years into how to answer these questions I feel much more comfortable calling myself a real teacher, rather than saying “I just teach English” which is the way I notice many people describe themselves at the beginning and/or if they don’t really identify with their work.

2.) How much you know means very little compared to how much you can convey: Unfortunately, even after I realized how much more I needed to prepare myself for difficult grammar and expressions, my first few lessons with each tricky topic didn’t always go well. Even though I knew exactly how I would explain a concept, my students weren’t always catching on and if you can’t help someone to understand what you’ve said than you really didn’t succeed in explaining.

Thus, I’ve learned a lot about my communication skills. I’ve learned how to assess a student’s comprehension not by the fact that they say ‘yes’ to having understood but by the intonation, hesitancy, and body language that accompanies a response (even when it’s ‘yes’). I’ve even gotten better at being able to read what kind of different explanation would work better for particular students because teaching really shows you how different our needs are. For example, some people prefer to have multiple written examples with repetitive sentence structure, others respond more to one detailed example that relates to their own life.

Thus, I’ve learned a lot about my communication skills. I’ve learned how to assess a student’s comprehension not by the fact that they say ‘yes’ to having understood but by the intonation, hesitancy, and body language that accompanies a response (even when it’s ‘yes’). I’ve even gotten better at being able to read what kind of different explanation would work better for particular students because teaching really shows you how different our needs are. For example, some people prefer to have multiple written examples with repetitive sentence structure, others respond more to one detailed example that relates to their own life.

3.) There’s a lot of power behind verb tenses: Until I started teaching, I gave very little thought to the difference between (1)”I exercise,” (2)”I will exercise,” and (3)”I would exercise” but there is SO much meaning packed into these choices that, especially as native speakers, we make almost unconsciously. In fact, each time we chose the (1)present tense over the (2)future tense we are assigning more reality to our statement (the future tense is really only a prediction in most cases, and predictions can change) just as each time we choose the (3)conditional tense we are giving away a lot of our ownership (the conditional tense implies that our statement is only true if the following condition is met, which is then far easier to write off as “not our fault” if we don’t follow through).

This is all theoretical in the classroom, but it got me thinking a lot about how it applies to my real life. How often do I say “I would make a salad if I had more vegetables” or “I’m going to be a writer one day”? The first example implies that getting more vegetables is practically not a possibility and therefore it’s out of my control that I can’t have the salad I feel I should have. The second takes away my need to make it a reality right now, as well as disallows me to identify with the title now, putting it off for the infamous ‘one day.’

4.) Connotations are everywhere and they’re not obvious to everyone: While teaching and correcting my students’ vocabulary choices I’ve realized that, so often, it’s not that the word they’ve chosen is inherently wrong it simply ‘sounds funny.’ Especially as someone who speaks to non-native English speakers regularly, the mistakes are often easy to understand but I want to ensure they know the “best, most natural way” to say what they want to say…which gets really tricky when it comes to direct translations that work, but sound odd or even rude.

4.) Connotations are everywhere and they’re not obvious to everyone: While teaching and correcting my students’ vocabulary choices I’ve realized that, so often, it’s not that the word they’ve chosen is inherently wrong it simply ‘sounds funny.’ Especially as someone who speaks to non-native English speakers regularly, the mistakes are often easy to understand but I want to ensure they know the “best, most natural way” to say what they want to say…which gets really tricky when it comes to direct translations that work, but sound odd or even rude.

For example, the most common way to say ‘my wife’ in Spanish is mi mujer which literally means ‘my woman.’ However, when we hear someone call their wife ‘their woman’ in English it sounds very possessive and, to many, inappropriate. But even explaining that it sounds possessive requires an explanation that THAT term is generally negative, too! Then think about that fact that Brits interpret ‘I’m fine’ as a normal, positive response whereas Americans tend to read ‘fine’ more as an inadvertent way to say you’re not okay and connotations only become all the more confounding! Where and when did we come up with these culturally-specific connotations? It’s fascinating as a human, but frustrating as a teacher.

5.) What we have words for in our language speaks volumes about our culture: Since my lessons are taught completely in English, I haven’t actually learned any foreign languages through the process of teaching. However, I’ve learned about a few different expressions and random words in Portuguese, Japanese, and German when my students have struggled to find an equivalent in English. Occasionally, it’s just a matter of them never having come across such advanced vocabulary in English but I’ve also realized that there are simply some complex concepts that we haven’t assigned a word to in English!

I’ve grown up hearing the anecdote that in the Eskimo language, there are 50+ words for snow and, while that ‘fact’ has been greatly debated over the years, it brings to light a very interesting reality—cultures DO place different degrees of importance on different topics and the differences between (what other cultures consider) ‘similar things.’ My Brazilian students have explained the concept of saudade to me and the best I could do to describe it is to say that it’s a deep missing or longing for someone dear to you, but there are many more nuanced connotations that come along with it. For me, it’s enough to say “I really missed you” whereas for a Portuguese speaker that doesn’t express the same depth as saudade.

I’ve grown up hearing the anecdote that in the Eskimo language, there are 50+ words for snow and, while that ‘fact’ has been greatly debated over the years, it brings to light a very interesting reality—cultures DO place different degrees of importance on different topics and the differences between (what other cultures consider) ‘similar things.’ My Brazilian students have explained the concept of saudade to me and the best I could do to describe it is to say that it’s a deep missing or longing for someone dear to you, but there are many more nuanced connotations that come along with it. For me, it’s enough to say “I really missed you” whereas for a Portuguese speaker that doesn’t express the same depth as saudade.

It’s the same way in which English speakers often use the word ‘awkward’ but this doesn’t exist in Spanish. Both examples raise the question of whether or not these sentiments can even exist in a culture that does not have a word for them. Could it be possible that Spaniards don’t feel awkwardness in the way Americans do or that English speakers don’t miss as deeply as Portuguese speakers? Examining language and the depths to which our culture goes to express something brings to the surface so many new questions to explore.

6.) You can choose the kind of person you are through the language you choose: You can preach all day about the importance of a positive perspective, how you believe in the law of attraction, how you’re the creator of your own reality, and so many other in-fashion catchphrases, but does the way you speak on a regular basis reflect that? Teaching English and therefore having others listen so critically to my words has made me realize that, in the less obvious ways I was NOT living up to my beliefs through my language. I believe I’m an empowered, sovereign being and so why do I keep talking about what I’d like to do, what could be possible in the future, and how I would act if circumstances were different?

Until I started teaching different verb tenses I didn’t realize how often we live in the conditional tense (which was the verb tense of my three examples above) as native speakers. And once I realized this, I started to notice how I didn’t like it. If I want to feel empowered, strong, and capable I need to choose not only those positive adjectives but also the nouns, verbs, and expressions that reflect them. What we say to ourselves and to others is the constant construction of who we are and I, for one, want to be a conscientious constructor!

I could go on and on about other insights I’ve gained from teaching English but I think I’ve already given you quite a lot to consider. If you’re interested in hearing a bit more about the complexities of the English language and how this has related to my adventures abroad be sure to check out the podcast interview I gave on this exact topic!

I could go on and on about other insights I’ve gained from teaching English but I think I’ve already given you quite a lot to consider. If you’re interested in hearing a bit more about the complexities of the English language and how this has related to my adventures abroad be sure to check out the podcast interview I gave on this exact topic!

Are you a teacher who has learned a lot about your subject and/or life in general from teaching? What other life lessons would be on your list?

Sincerely,

Dani